History

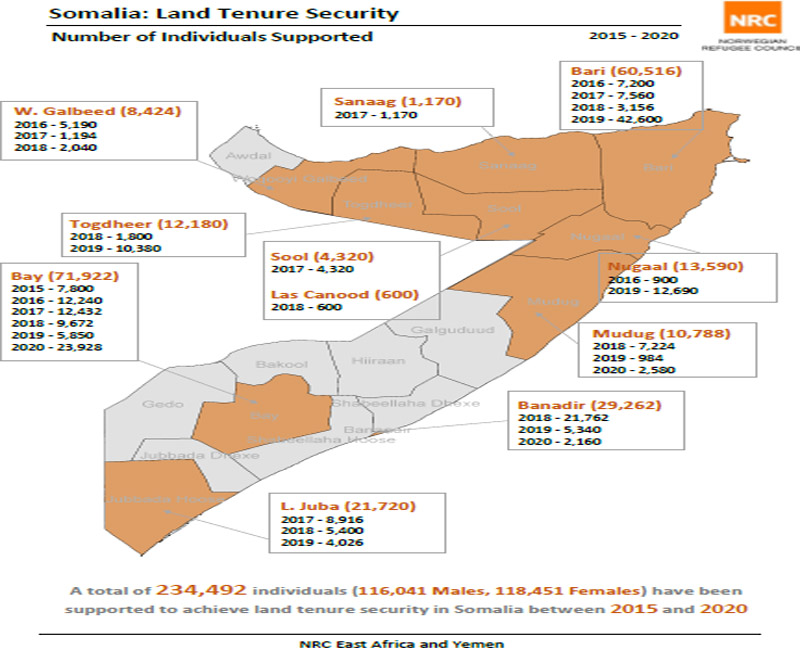

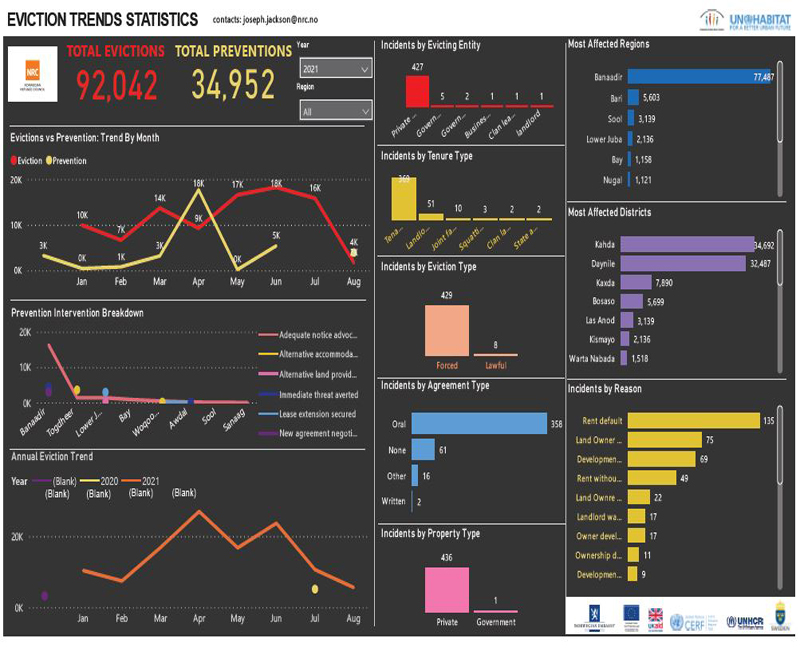

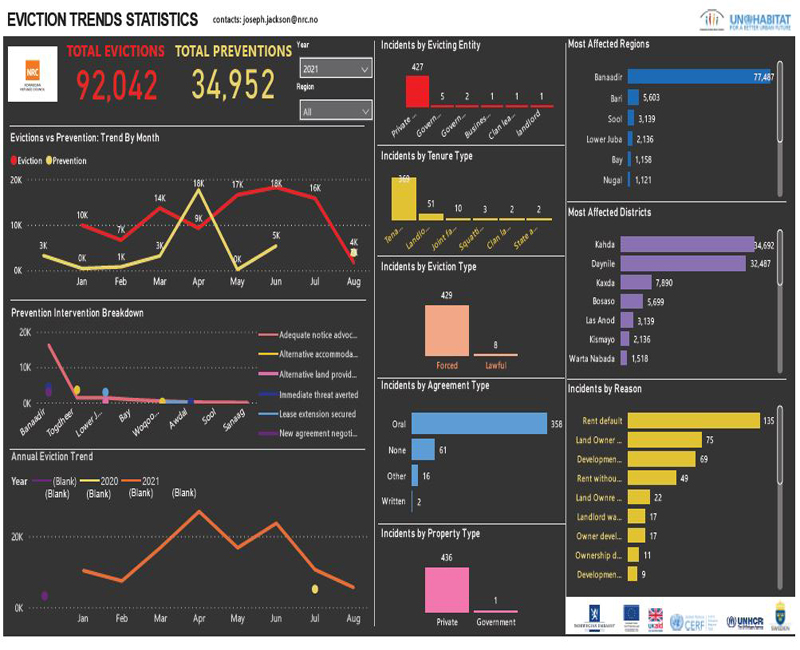

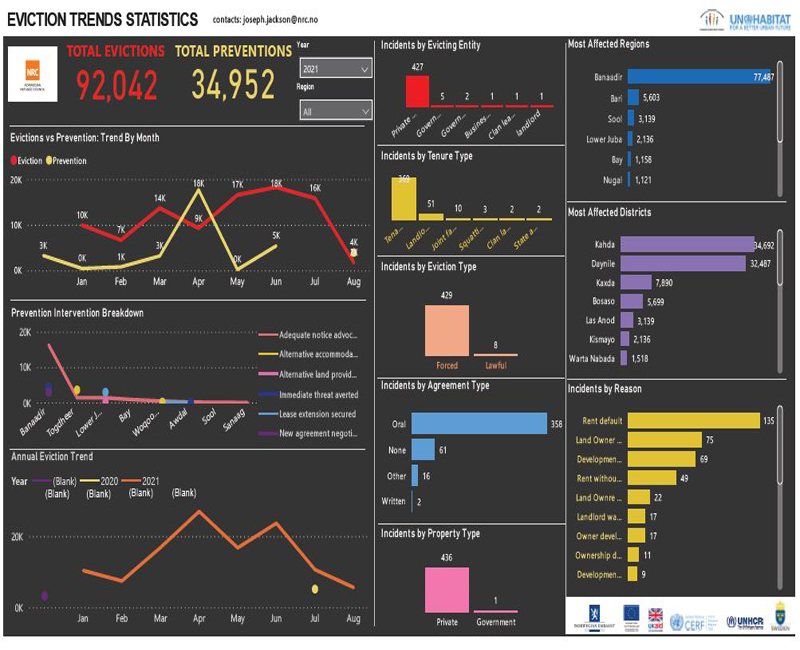

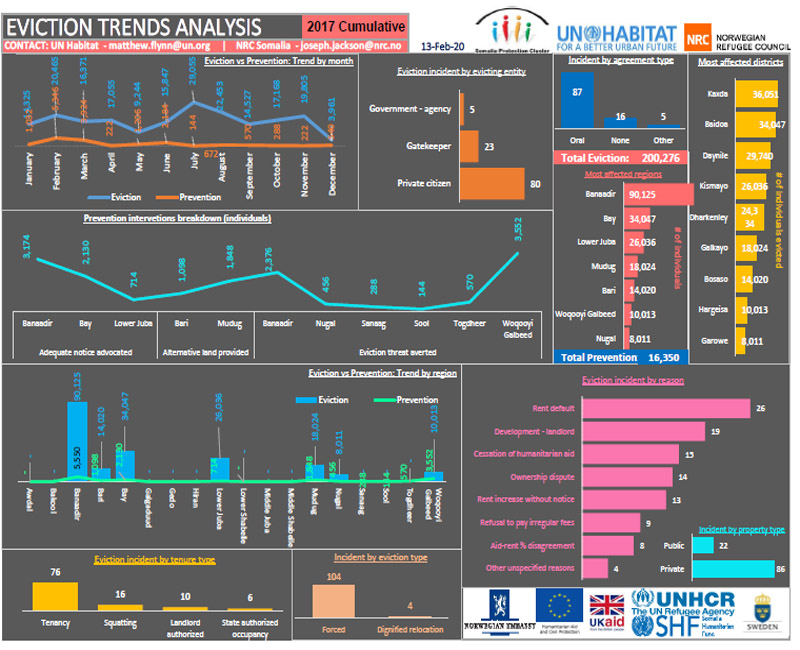

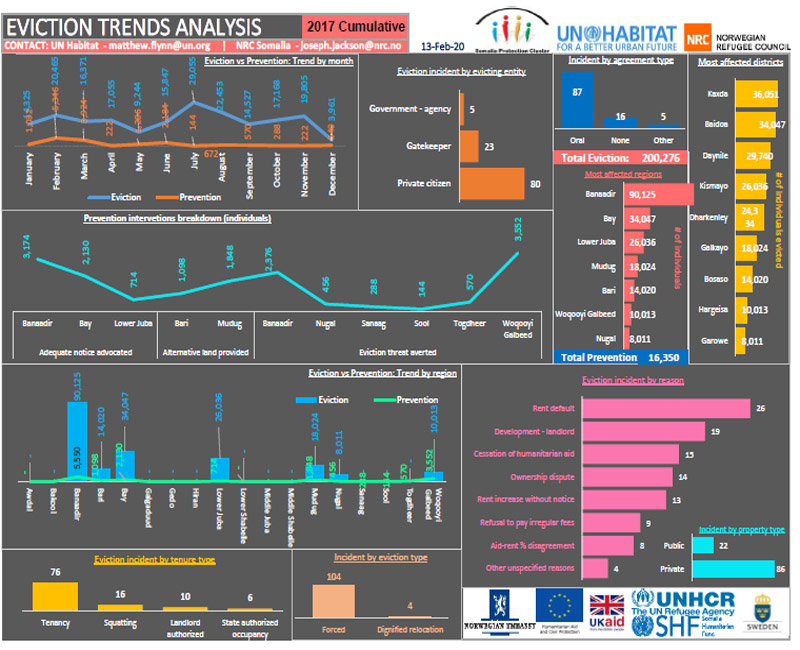

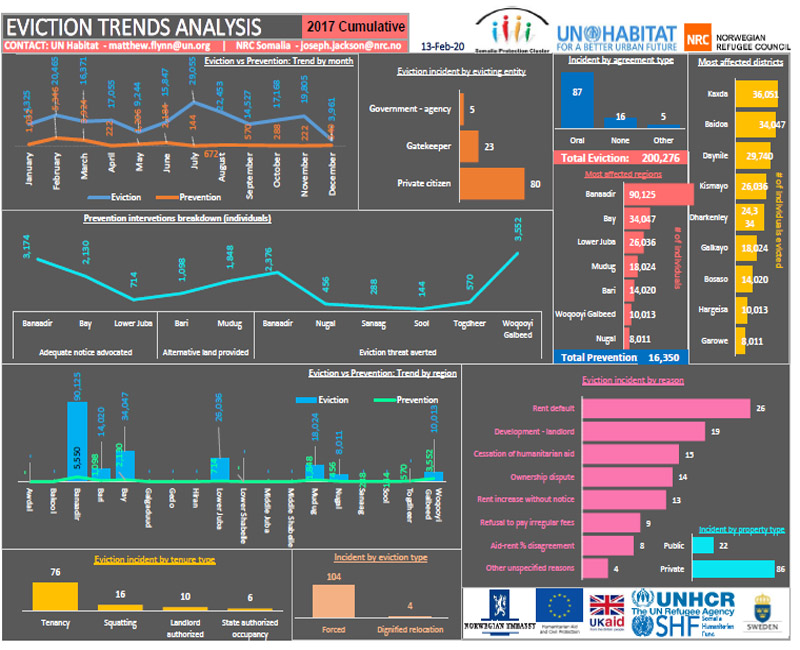

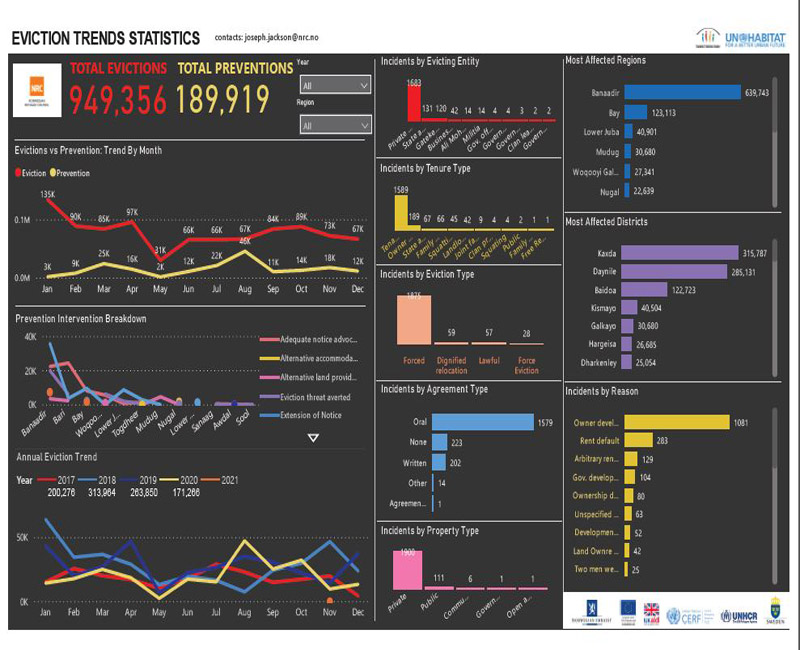

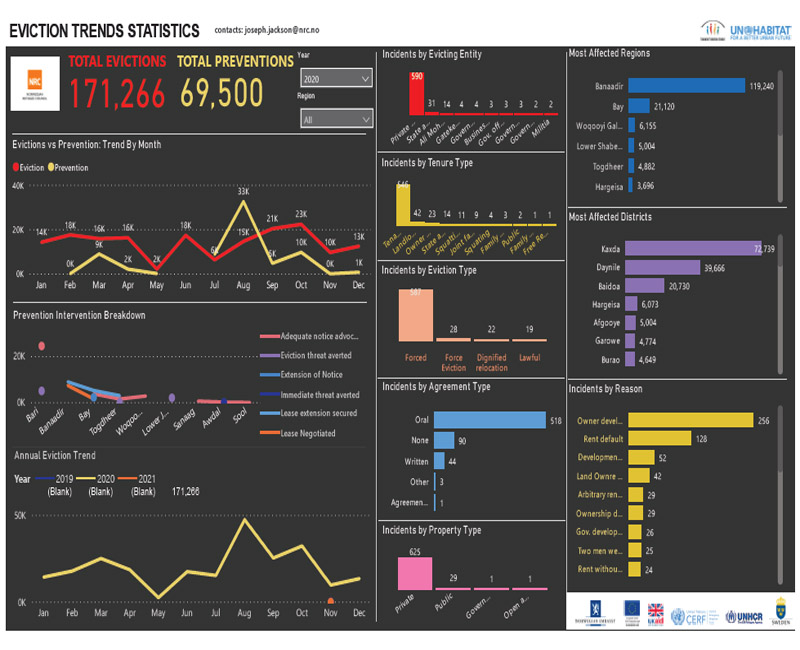

Forced eviction is a phenomenon that violates the fundamental civil, political, economic, social and cultural rights of individuals and groups. It does grave harm, and the consequences range from secondary displacement and total destruction livelihood strategies to disruption of established life routines. International law stipulates that every person or group of persons that is threatened with forced eviction should have full recourse to due process or other forms of remedy to protect their fundamental human rights. Unfortunately, in most cases, displaced communities are not afforded such an opportunity, and eviction incidents are often characterised by right violations ranging from limited or no notice period to forced removals. The Norwegian Refugee Council began documenting incidents of forced evictions in Somalia as far back as 2015, when field teams across the country observed a persistent surge in the number of incidents. A preliminary crunching of the initial dataset quickly established an alarming trend among disproportionately IDP populations which prompted NRC to engage more systematically. A pilot initiative was launched shortly to better understand the phenomenon. But what started mostly as a manual and fragmented initiative with a small group of NRC ICLA team in Mogadishu, South Central Somalia, rapidly evolved into a well-coordinated system across the country with standardised processes and procedures. The system transitioned from an MS Excel-based platform to a Power BI infrastructure, and is now a full-fledged user-friendly web portal with geo-mapping capability and other vital features. .

Methodology and limitations

NRC has deployed a little over 40 skilled and highly trained paralegals leveraging robust local networks to monitor, document and report incidents of evictions across Somalia. The collection of eviction data is also being supported by UNHCR-funded Protection and Return Monitoring Network (PRMN), the CCCM cluster, a selected number of protection partners, and a network of community volunteers. Incidents are verified on-site through direct contact with the affected communities and local authorities. However, while these statistics are representative of significant trends and patterns, the following caveats remain. First, they do not include all evictions, particularly small-scale household level incidents. Second, they cover only accessible locations where NRC and its collaborating partners maintain active operational presence. Lastly, the actual number of persons could be more or less because the number of individuals is estimated at six, representing the standard household size for humanitarian planning in Somalia. The eviction programming framework currently operational in Somalia embodies three central pillars. The first pillar, monitoring and reporting, is intended to inform humanitarian planning and advocacy, and trigger to specific protection responses. The prevention or aversion pillar seeks to achieve five objectives - adequate notice advocated, alternative accommodation facilitated, alternative land provided, eviction threat averted, and/or lease extension secured. This pillar consists of six non-linear processes, beginning with eviction threat alerts and possibly ending with a facilitated dignified relocation. The third pillar is post-eviction cash assistance – a limited financial support given to victims of forced eviction to help with cope with post-incident stress. .

Post-eviction cash assistance

In addition to secondary displacements, forced evictions are often carried out employing physical violence, which leads to the disruption of established life routines and destruction of livelihood and other HLP assets. Victims are often faced with high protection risks following an eviction incident and require immediate emergency protection support. Under pillar three of the eviction framework, a limited amount of financial assistance is provided to victims of forced eviction help them cope with post-eviction complications. The package consists of three key elements: i) emergency physical security support to cover rent; ii) transportation facilitation; and iii) cash subsidy to address other emerging emergency needs. It is usually a one-off payment made to eligible beneficiary households who are selected based on vulnerability. .